In August of 1942, Walt Disney released the classic animated film, Bambi. When it was rereleased some years later, my mother took me on a rare outing to see it. I must have been around eight years old. Today it’s considered one of history’s most controversial films.

In August of 1942, Walt Disney released the classic animated film, Bambi. When it was rereleased some years later, my mother took me on a rare outing to see it. I must have been around eight years old. Today it’s considered one of history’s most controversial films.

Some viewed it as a metaphor for the treatment of Jews by the Nazis. Hunters saw it as an anti-hunting insult to American sportsmen. A writer for Audubon praised it for raising environmental consciousness and compared its impact to Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s impact on views of slavery. As a practical nurse who’d seen more than her share of life and death, my mother may have been bothered by the violence, but I suspect she told herself it was an essentially harmless children’s cartoon about the way life is.

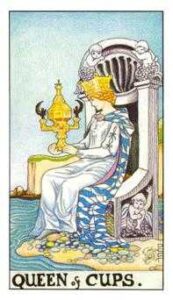

I was horrified when Bambi’s mother was killed by hunters. To learn that mothers can die while their children are young. That some men enjoy killing animals. That people can carelessly destroy the homes of thousands of innocent animals. That magnificent, antlered stags are kings of the forest. I wondered where the queens were.

There was one lesson I never forgot. Remember Thumper’s shy innocence when he said his classic line: “If you can’t say somethin’ nice, don’t say nothin’ at all”? Thumper’s advice became my sacred mantra. Whenever I repeated it in his sweet voice my mother would chuckle. I reveled in her attention and approval.

I was taught by my parents, church, and school to be sweet, kind, gentle, forgiving. Nice. Good. But what my mother and I saw as virtue was, in reality, repression. Of my emotions. My voice. My souls’ truths. And my belief in my own worth.

Was I learning to be a nice girl or a good girl? And according to whose definition? The boy in my 7th grade class? Felix Salten, the author of Bambi? Thumper? Walt Disney? My mother? My father? My church? Or the truths of my own soul? By denying our fear and anger my mother and I thought we were being spiritual and noble. In truth we were normalizing our culture’s obsessive drive for power and control and its dismissive attitudes toward women and individual responsibility.

Where love reigns, there is no will to power; and where the will to power is paramount, love is lacking. The one is but the shadow of the other. C.G. Jung. On the Psychology of the Unconscious, CW7, par. 78

I grew up wanting to be loved and worthy. I believed that the values of my family were the correct ones, and that obeying them was the way to happiness. But deep within, the Self knew I was wrong and warned me by way of a recurring dream. In it I couldn’t talk in a public situation because my mouth was full of sticky pebbles I couldn’t get rid of.

Now I know that the real reason I stifled my voice for so long was not due to noble intentions. It was fear. I’ve seen what happens to angry women who dare to speak up about injustice and abuse, and I’ve been afraid of being targeted. Not just by men, but also women. And most of all by the God-image I was raised to believe in: a god whose name is invoked by many religious authorities—not all, thank goodness—to justify repressive attitudes toward women. So when a friend suggested I write about misogyny, I was initially reluctant. But I decided to do it for myself and for all infected with the poison of misogyny.

We need to recognize our habitual ways of thinking about the masculine and feminine principles. We need to see that they exist in all of us. We need to stop defining them in terms of binary genders. To stop legislating how they should manifest in us according to double standards based on outdated gender stereotypes.

Carl Jung wrote:

Woman’s psychology is founded on the principle of Eros, the great binder and loosener, whereas from ancient times the ruling principle ascribed to man is Logos. The concept of Eros could be expressed in modern terms as psychic relatedness, and that of Logos as objective interest.” C.G. Jung, CW 10, par. 255

Logos is the principle of discrimination, in contrast to Eros, which is the principle of relatedness. Eros brings things together, establishes cyanic relations between things, while the relations which Logos brings about are perhaps analogies or logical conclusions. It is typical that Logos relationships are devoid of emotional dynamics. C.G. Jung, Dream Analysis Notes o the Seminar Given in 1928-1930 (25 June, 1930), p. 700.

Logos and Eros are qualities of the left and right hemispheres, respectively, of our brains. This means that every single person, regardless of gender, contains all these traits, and many more. Next week I’ll suggest ways we can use them in service to healing the poison of misogyny. Meanwhile, I hope you’ll keep sharing your stories.

Jean Raffa’s The Bridge to Wholeness and Dream Theatres of the Soul are at Amazon. Healing the Sacred Divide can be found at Amazon and Larson Publications, Inc. Jean’s new Nautilus Award-winning The Soul’s Twins, is at Amazon and Schiffer’s Red Feather Mind, Body, Spirit. Subscribe to her newsletter at www.jeanbenedictraffa.com.

6 Responses

Your teaching is, as always, instructive, my dear Jeane. I am amazed at how fascinatingly you analyze your childhood. I must also admit that I mostly held back my words as a child. Although that may have other reasons, such as my mother’s silence about my father’s death (she lied to us and said that he was travelling)) or something else I don’t know. I still have difficulty expressing myself verbally. However, I will be excitedly waiting for your next article.🥰🌹

Thanks, Aladin. I don’t know why I have such strong memories attached to intense childhood emotions, but I do. My inner life has always been active and I was aware of it even as a child. Probably because I was often alone, without a lot of competing noise or distractions. We had no television sets or cell phones in those days! Also because, like you, I experienced a childhood trauma: my parents’ divorce closely followed by my father’s death. Things like that can mark a person for life! It’s only in retrospect that I see how the strongest memories are clues to the mystery of myself, and that they tend to cluster into a few meaningful themes. It’s like putting a jigsaw puzzle together until meaningful images emerge. For me, this is fun and comforting. I think I was born to understand and find meaning in my life, and when I found Jung I knew I’d found my teacher and guide. 🙂

Dear Jeanie,

While my mother didn’t die in body, she perished in spirit from all the abuse inflicted on her by my father (up until her death three years ago), which is why I also remember reacting with immense shock and sadness over Bambi’s mother’s death. I couldn’t articulate it at the time, but at six years old watching that film, I somehow realised that even though I lived with a mother, I was without one.

Instinctively, I looked for other mothers in books, lovers and friends, making sure I received a little of that missing love. Slowly in my thirties, I began to mother myself and rely on others less. Slowly in my fifties, I began to release true voice and share my words and experiences with the world. It’s taken all of my life to come full circle and know myself for the first time … a nod to T. S. Eliot here!

Like Aladin, I didn’t talk much as a child either and had speech issues, including a stutter. I saw a language specialist to improve my pronunciation and speech for several few years. It’s fascinating how challenging words were from the very beginning of life, where my father stole my words, and how important they soon became, alongside learning how to mother myself, in order to re-claim them.

With love and hope, Deborah

Oh Deborah,

Your clear, straightforward voice brought tears to my eyes. I’m overwhelmed by its power. Like a key, it opened a locked door in my heart I haven’t known was there. Inside were words I’ve been unable to say until now:

“Even though I lived with a mother, I was without one.”

Thank you for this gift of insight, Lady Lightbringer.

Love and hope, Jeanie

Jeanie, I’m ab-soul-utely delighted that our words have spoken to each other today. For I remember that heart-breaking scene so well in Bambi and now only today, I understood why. Thank you so much for every kind word you ever said about my writing, (they’re tattooed on my heart!). x

You are most welcome. And thank you for the same.