The other day I read an article on the internet about a mostly male mindset called the “culture of honor” which places such a high value on defending one’s reputation that it results in more risk-taking and accidental deaths. Reportedly, this way of thinking is most prevalent in small towns and rural areas of the South and West in such states as South Carolina, Wyoming, and Texas. I wondered: What myth inspires these unfortunate men to take such dangerous risks that they are killing themselves? Why do they follow it? I found my answer in the wisdom of two of my favorite authors: Joseph Campbell and Carol S. Pearson.

The other day I read an article on the internet about a mostly male mindset called the “culture of honor” which places such a high value on defending one’s reputation that it results in more risk-taking and accidental deaths. Reportedly, this way of thinking is most prevalent in small towns and rural areas of the South and West in such states as South Carolina, Wyoming, and Texas. I wondered: What myth inspires these unfortunate men to take such dangerous risks that they are killing themselves? Why do they follow it? I found my answer in the wisdom of two of my favorite authors: Joseph Campbell and Carol S. Pearson.

Campbell tells us that classic hero myths feature powerful male warriors who slay dragons to prove themselves and become masters of the world. Instead of recognizing this as a metaphor for the ego’s heroic struggle for consciousness, patriarchal cultures have tended to take it as a literal model for external achievement, encouraging people to climb to the tops of hierarchies where they can define what the heroic ideal is and decide who is entitled to it: usually the few. We see the dark side of this interpretation in ruthless political leaders and business moguls who deliberately spread lies and foster conflict and hatred to keep their money and power rather than trust the masses enough to share with them.

Pearson describes another unhealthy consequence: “focusing only on this [interpretation of the] heroic archetype limits everyone’s options. Many…men, for example, feel ennui because they need to grow beyond the Warrior modality, yet they find themselves stuck there because it not only is defined as the heroic ideal but is also equated with masculinity. Men consciously or unconsciously believe they cannot give up that definition of themselves without also giving up their sense of superiority to others — especially to women.” Pearson gives the example of the main character of Owen Wister’s book, The Virginian, who leaves his bride on their wedding day to fight a duel for honor’s sake. Why? Because the only other role available to him is the victim, or antihero.

An obsession with the hero-kills-the-villain-and-rescues-the-victim plot distorts healthy heroic behavior (having the courage to fight for ourselves and change our worlds for the better) into the dangerous “culture of honor” ideal we see among the young working-class and minority men who still embrace it in many parts of the world. Isolation, impoverishment, religious fanaticism, social disenfranchisement and inadequate education all feed this mentality. The only thing apt to change it is the awareness that not everyone thinks this way and there are healthier alternatives.

Pearson’s research in the 1980’s revealed that women were rediscovering the true meaning of the dragon-slaying myth. Their story in which there are no real villains or victims — just heroes who bring new life to us all — is being adopted by males and females alike. While the timing and order may be slightly different for men and women, we all go through the same basic stages of growth in claiming our heroism. “And ultimately for both [genders], heroism is a matter of integrity, of becoming more and more themselves at each stage in their development.” This is the Jungian path of individuation.

The heroic, self-disciplined quest to avoid the inauthentic and the superficial conquers the slumbering dragon of unconsciousness and births the courage to be true to one’s inner wisdom. An individuating person knows, in Pearson’s words, that “assertion and receptivity are yang and yin — a life rhythm, not a duality.” Freed from the tyranny of conflict between opposites, such a person names our divisiveness and promotes care, cooperation, compassion, community and unity. Do you know someone who fits this description of an authentic hero?

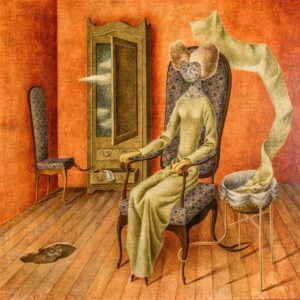

Life and Love in the Midst of Death

I’ve been recording my dreams since 1989. I called this one, “Life and Love in the Midst of Death.” Dream #423

0 Responses

Odd though this comment may seem, this post reminded me of Stephen King, when he said something like – Harry Potter is about the struggle of good to triumph over evil, while Twilight is about the importance of having a boyfriend. Yet I think the power of the Twilight books doesn’t rest on romance, but on the individuation of its characters in the context of growing up and relationship.

I don’t know if you have any thoughts on that…I shouldn’t presume that you’ve read or enjoyed either series of books.

Hi Heather,

Actually, I have read, and loved, the Harry Potter series and agree with Stephen King that it is about the struggle of good to triumph over evil — if we consider good, as Jung did, as becoming individuated and enlightened, and evil as the many obstructions one meets along the way, including a misplaced external emphasis on power, status, and materialistic acquisitions, along with our own unconsious inner enemical forces of sloth, ignorance, and the raw instincts in their unconscious, unmodified, and therefore extremely dangerous forms.

I haven’t read the Twilight books (is there a movie or TV series about them too?) and so cannot compare them, but if, as King suggests, the overriding plot is about teenagers trying to get and keep boyfriends and the obstacles they experience in the process, then I suspect he may be at least partly right. On the other hand, could it be that the plots are written in terms that adolescents can relate to, but that the underlying theme of good conquering evil still prevails? If so, perhaps it’s a step along the way for young minds that cannot relate to the ultimate meaning of the hero’s journey but are beginning to get glimpses of some of the challenges it might entail.

This is pure supposition on my part. I should probably check out the Twilight books of they are making such a big impact on our youth.

Thank you so much for bringing up this very original and thoughtful question. Can anyone else say more about this?

Best,

Jeanie

Hi Jean,

Here are the reflections that came after reading your piece. I love your passionate call to action through initiation.

As the storm approaches, I think of the many people searching the city streets and surrounding woods for the homeless, trying to gather them in. I think of the people checking in on their elderly neighbors. I watched a group of teenagers and some adults sand bagging a flood-prone street.

Fire and water are the great purifiers—Kali’s cleaning supplies. As the storm scours the cities, selfishness washes away as neighbor helps neighbor, and city workers begin collecting loose trash from the streets. Anything that can fly away is removed and suddenly, hours before the storm hits, the streets are cleaner than they’ve been in years.

Initiations into the realms of the soul, the source of every storm and peace, occur in times of disasters. Candles are lit. Simple meals are prepared. Flowers are taken in that would otherwise be strewn across the lawn, and arranged in vases and placed in the center of the table. Finally adults wake up and protect their young. Finally they give teenagers examples to follow. Great feats of strength are performed with shovels and the passing of sand bags into each other’s arms. The young man buys milk for his sickly grandmother when he would much rather play with his Xbox. People lift their faces from behind computer screens, look at each other, and remember. No more being lost in their own worlds. There are jobs to do and do together. Where are the birth certificates and the passports, the mortgage, and the insurance policies? Do we have enough food and water? All of these little initiations into the family and the community, leaving behind, at least for a while, the petty, self-centered storms that we unleash on each other.

Hurricane Irene, goddess of peace, and gate keeper of heaven, knows the only way to rouse us into peace is to team up with Kali and ravage us with a storm. And the heroes and heroines that rise and reach for the weak, holding them in secure arms, giving them refuge, will be unheralded citizens in houses and shelters all along the East Coast. And each act of kindness and bravery, each act of unselfish giving will initiate both giver and receiver into long forgotten places in the soul. Places we all need to tend and to share.

Joseph,

You bring up an excellent point about how a disaster can bring out the best in us. The brilliant Jungian M. Esther Harding has said that wars can also encourage human growth. Whatever our egos haven’t learned can be attained only by a heroic deed that transcends the ego awareness of the collective group. Thus, when people fight not for themselves and their own prestige but for the good of mankind, the old, less aware ego acquires a new supreme value that benefits all.

Thanks, as always, for your thoughtful response.

Jeanie